If you grew up reading primarily DC Comics during the Silver Age (National Periodical Publications in those days, rather than DC; I’m focusing on the 1960s when I say Silver Age), you were accustomed to a far different sort of comic book storytelling than we’re seeing nowadays in what I’ll call, for simplicity’s sake, the Graphic Novel era. (I’ll posit that this era has many overlapping names and motifs, but the lowest common denominator seems to be long-form storytelling, thus graphic novel.)

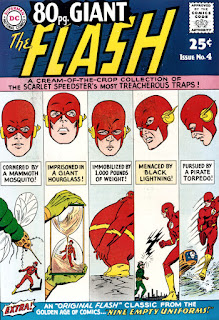

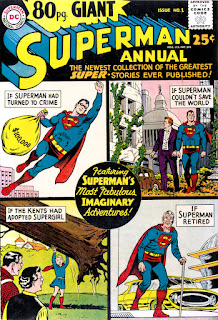

You would’ve been familiar with the 80-page Giant issues, which were priced 25 cents and compiled stories from the past and typically focused on a single theme. For example, I recall a Superman Giant issue whose stories focused on the different colors of kryptonite; a Jimmy Olsen Giant issue featured several of the strange transformations Superman’s pal had undergone over the years. (I won’t go into those changes, but you can click here for an article that describes 15 of those stories—and it’s absolutely appropriate that the word bonkers is in the essay title. Gregor Samsa never had so much fun, but Jimmy Olsen never experienced much existential angst before the reader reached the letters column.)

This rambling preamble boils down to a simple statement:

These Silver Age comics were intended to be fun and had little to do with the

real world (except occasionally: Jimmy Olsen infiltrated a gang of juvenile

delinquents and learned Perry White’s son was a member in "Jimmy Olsen,

Juvenile Delinquent!"; it appeared in the October 1959 issue of Jimmy’s

comic). The superhero stories were diverting tales focused on good guys

battling bad guys and often incorporated elements lifted from pulp science

fiction magazines.

If the sharp swerve into noirish (nightmarish?) superheroics

initiated by Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight in 1986 was preceded

by a long transition period launched with Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams’ grittier

takes on Batman and the socially conscious/relative Green Lantern/Green Arrow

team-up starting in 1970, we can perhaps describe the Silver Age DC era as a

pastoral superhero age.

This latter world is the sort of setting that anchors Dwight

Decker’s novel The Arsenal of Wonders. (It’s worth noting the book’s

title echoes that of The Arsenal of Miracles, a 1964 SF novel by Gardner

F. Fox, one of DC’s most prolific scripters during both the Golden Age and the

Silver Age.) Using tropes familiar to fans of the Silver Age, Decker builds a

universe about a superhero who is displaced in time and in space.

Decker introduced Astroman, the hero of this book, in a

prior novel, The Secret Citadel. Matt Dawson was thrown into a parallel

Earth thanks to a lab experiment gone awry. This new Earth is very like Matt’s

own except that it’s 1967 and superheroes and supervillains are among those who

populate the world. Matt gains some powers of his own because of his

dimensional transition.

In this novel, Matt and Astrogirl travel through space and

time to visit Helionn, the planet from which Astrogirl and Astroman came to Earth.

They must go back in time to visit the planet because it exploded years ago.

They travel to Helionn to find a legendary arsenal that will

help them battle an arch foe, Garth Bolton, whose crime spree is expanding as

it exploits the disappearance of Astroman.

If this sounds familiar—like the origin story of Superman

and the fodder for many Silver Age tales in which Kal El visited Krypton or

viewed scenes from its past—then understand that Decker is writing homage. This

novel is an extended letter of thanks and loving respect to all those creators

who built, story by story, the remarkably rich universe the Silver Age heroes

inhabited before it was exploded—quite literally—by the Crisis on Infinite

Earths (presented in a 12-issue series published in 1985 and ’86) and

subsequent Crises and . . . assorted other continuity-busting reboots (by

whatever names) that successively dilute the iconic legends established during

the Silver Age and based on the Golden Age versions of those heroes and stories.

As homage, this is not an explosion-illuminated tale cuing

up life-or-death battles in every other scene: in other words, this is not

comparable in any way to a movie in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Just as it

took decades for the details of Superman’s canon to accrete to the Man of

Steel—Smallville, Krypto, the many colors of kryptonite and its multifarious

radiations, the Fortress of Solitude, Kandor the bottled city, Lori Lemaris,

Jimmy Olsen’s signal watch, Supergirl, the Legion of Super-Heroes, and on and on—Decker’s

tale is a more leisurely stroll through the inventories of SF tropes used in

countless sword-and-planet and space opera novels and stories from the time of

Edgar Rice Burroughs’ A Princess of Mars (1912) through the 1960s—and

beyond, really, if you consider how Star Wars was influenced by pulp

fiction and Hollywood serials.

If you occasionally are swept by nostalgia for a simpler era of comic book storytelling, for heroes untainted by shades of gray and who knew good from bad—for heroes who were heroic—you may enjoy The Arsenal of Wonders. Reading it is an experience much like that of Matt Dawson: a trip through time and space.

It's available from Amazon at this link.